Bringing law school to the north

December 04, 2024

Twenty years later, graduates of UVic Law’s Akitsiraq program are key players in the Inuit legal landscape.

Aaju Peter had a big decision to make. She had intended to sign her son up for an innovative new program connected to the University of Victoria that promised to keep law students in Nunavut, instead of heading south. But it turned out that he was not eligible.

Peter was born to an Inuit family in Arkisserniaq, Greenland and married an Inuk from Canada. In the early 2000s, she was already an accomplished clothing designer and multi-lingual translator. She made a bold move that would change her future path.

“I had originally gone to enrol my son in the program, but I was told that at 18 he was too young to be considered,” says Peter. “I didn’t even know that I was interested in law at the time, but because they dared to tell me that he was too young I thought—‘Well, I’ll do this myself.’”

The Akitsiraq law program accepted its first cohort of students in 2001, including Peter. The program was named after a place on the northwestern tip of Baffin Island where for generations traditional Inuit “courts” met to address conflicts in their community. In Inuktitut, Akitsiraq also means “to fight back.” Now, 20 years since the class convocated, the program’s graduates continue to fight back—persevering against historical underrepresentation and systemic barriers.

New territory needed lawyers

The formation of Nunavut in 1999 created a new territory governed by Inuit. This historic event was the result of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, which aimed to address long-standing issues of land ownership, self-governance and cultural preservation for Inuit. However, with the establishment of Nunavut came the realization that the territory faced a critical shortage of Inuit legal professionals.

“The land-claim agreement committed to something called representative Inuit employment, which meant not only should Inuit be in the government workforce in numbers proportional to their representation in the population, but they should be in every level of leadership in the territory,” says Kelly Gallagher-Mackay, who was the Northern Director of the Akitsiraq Program in 2001.

Gallagher-Mackay worked with several Inuit who were involved in the justice system, and with local lawyers and judges to create the Akitsiraq Law Society. The group advocated with different levels of government to forge a program that would allow Inuit students to earn a law degree from UVic within their home territory. The resulting program was a partnership between UVic, the Akitsiraq Law School Society and Nunavut Arctic College.

In 2001, Nunavut had about 25,000 residents. More than 60 Inuit applied be part of the first cohort, and 13 were accepted.

“Students were in this kind of fishbowl as the first group to have the opportunity to earn a law degree in Iqaluit. Law school is challenging enough for any first-year student, but these students were under pressure and scrutiny from those who weren’t confident the program would be successful,” says Kim Hart, then Southern Director of Akitsiraq.

As few, if any, applicants had an undergraduate degree or had taken the Law School Admission Test—a requirement to being admitted to UVic Law—applicants were evaluated on previous experience and capacity to take on the rigour of the curriculum.

The Akitsiraq Law Program was designed to ease challenges faced by Inuit students who pursued legal education in southern Canada. Many of these students struggled with isolation, financial difficulties and cultural dislocation, leading to high dropout rates. By offering a law program within Nunavut, the Akitsiraq initiative provided students with the support and resources needed.

Blending Inuit and Canadian law

Hamar Foster, who taught criminal procedure to the Akitsiraq cohort, faced the challenge of designing courses that conveyed Canadian law while being relevant to Nunavut. Unlike UVic courses that reference southern cases, the Akitsiraq curriculum used Nunavut legal cases to illustrate Canadian principles, often incorporating anthropological oral history to provide local context.

“We often naturally stress what a great program it was for the students, but it’s also true that it was a magnificent experience for those of us who volunteered to go and teach,” recalls Foster, a UVic professor emeritus of law.

UVic law professor John Borrows was excited to be a part of a school that could ensure Inuit students receive an education in their own territories.

Courses were designed to ensure the same standards as the southern curriculum. At the same time, Inuit knowledge, Inuit traditional law and ways of knowing and being needed to be integrated.

Borrows, who is a member of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation in Ontario, taught a class dealing with trans-systemic contract law. He notes how the students’ own experiences enriched the curriculum, creating an environment that fostered discussions about the intersection of Canadian and Inuit law.

“It was wonderful how they took charge of their own education. Many of them were Inuktitut first speakers, so they would often ask for clarifications and talk amongst themselves about what it was that I was teaching. They really were active learners in that space,” says Borrows.

Challenges to overcome

Many students were juggling family and community responsibilities or had significant financial challenges in addition to the demanding courseload of a four-year law degree. For Kim Hart, ensuring that students who needed support were able to access it was a crucial way of increasing their likelihood of success.

“If you don’t have support, or if you need to focus on things like paying your rent or putting food on the table—you just aren’t going to be able to focus on learning,” she says.

For Aaju Peter, these challenges came to a head in her second year. “I had to go to Kim Hart and say, look, I can’t continue this. I’ve sold everything I have, and I can’t afford to go to school anymore,” says Peter.

Financial support was important to the success of the cohort, but so was reaffirming the role of Inuit culture in the continuing work of the students as lawyers. For Peter, having an Inuit elder who specializes in Inuit traditional law was a crucial part of her learning.

For the final two years of the program, Lucien Ukaliannuk, a respected elder familiar with community justice, human rights and legal terminology issues, was invited to be the program’s Elder-in-Residence on a part-time basis.

“Lucien brought traditional values, perspectives and Inuktitut into the classroom, but… was also there as a sounding board. The students had someone with whom they could talk, with whom they could vent, and I think that was absolutely critical to retaining the students in the program and to their ultimate success,” says Hart.

The Continuing Influence of Akitsiraq

The program was a big success. In 2005, 11 students graduated with a fully-accredited law degree in a convocation ceremony held in Iqaluit.

“UVic very much was a place that taught a lot of us that you could think outside the box, that you could use the tools of law to change the system—Akitsiraq is a prime example of that,” says Gallagher-Mackay, Northern Director.

“For me, Akitsiraq is so close to my heart. It feels like the most meaningful accomplishment in my professional life. It was an amazing program, and the people who initiated it, taught, participated and supported it in so many ways were incredible to work with,” says Hart. “The students were just so accomplished and determined. I feel connected to each and every one of them. The program’s success was important, not only for its graduates, but for the Faculty of Law and for the territory. It has had such a lasting impact and legacy.”

“Before I got my law degree, I was not as respected by the western system that values positions like doctors, lawyers and professors. Once I got my titles, such as Aaju Peter, lawyer and Aaju Peter, Order of Canada, the system that values these titles started to value my words and my presence, even though I was still just a mother of five speaking on Inuit language, cultural and hunting rights,” reflects Peter.

The success of the Akitsiraq Law Program greatly influenced how UVic Law has integrated Indigenous legal education into its curriculum and program offerings. In 2018, UVic launched the world’s first joint degree program in Canadian Common Law and Indigenous Legal Orders.

“As we developed that program, one of the sparks of inspiration was the Akitsiraq program because it was an example of teaching Inuit law alongside Canadian law. We thought it would be wonderful if there was a degree that more generally put Indigenous legal traditions into conversations with Canadian legal traditions,” says Borrows.

—Katie McGroarty

Where are they now?

The 2005 Akitsiraq graduates

Lillian Aglukark

Prior to being accepted into the Akitsiraq program, Aglukark worked for Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., as well as other Inuit organizations. In 2009, she joined Ahlstrom Wright Oliver and Cooper in Edmonton as the only Inuk representing residential school Survivors through their claim-arbitration hearings, conducting hearings in Inuktitut. She was called to the Northwest Territories bar in 2008 and to the Nunavut bar in 2009. Aglukark served as part of the Commission’s legal council on the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) and conducted hearings in Inuktitut along with fellow Akitsiraq graduate Qajaq Robinson. She is a board member of Pauktuutit, a non-profit representing Inuit women in Canada.

Siobhan Arnatsiaq-Murphy

Arnatsiaq-Murphy worked for the Nunavut Department of Justice as a policy analyst before studying law in the Akitsiraq program. Post-graduation, she articled with Nunavut’s Department of Justice. In addition to practising law, Arnatsiaq-Murphy has performed traditional Inuit drum dance and worked as a choreographer for over 20 years.

Henry Coman

Coman spent eight years as an RCMP officer in the North before the Akitsiraq program. After graduation, he articled with Justice Canada in Iqaluit before being called to the bar in 2009. In 2007, following a year of articling, Coman was deployed in Afghanistan where he was part of a team training the Afghan National Police Force. Coman retired from the RCMP in 2018 and has worked within the Government of Nunavut as deputy director of Corrections, director of Civil Forfeiture, associate deputy minister for the COVID-19 Secretariat and more. He is currently an associate deputy minister at the Devolution Secretariat, which is part of Executive and Intergovernmental Affairs.

Susan Enuaraq

Before studying law, Enuaraq was a former assistant director of community justice for the Nunavut Department of Justice. After graduation, she articled with Justice Canada in Iqaluit before being called to the Nunavut bar a year later. Enuaraq served as legal counsel with the Public Prosecution Service of Canada. In 2013, she was appointed dean of Nunavut Arctic College’s Kivalliq campus, following two years of teaching law in Iqaluit.

Kunuk (Sandra) Inutiq

Before beginning the Akitsiraq program, Inutiq was a policy analyst in the government of Nunavut. After graduation, she articled with Nunavut’s Department of Justice. In 2006, she became the first Inuk woman in Nunavut to pass the bar exam. She has worked as legal counsel for the government of Nunavut, as director of policy for the Office of the Languages Commissioner as well as serving as the Official Languages Commissioner for Nunavut. Inutiq was also the director of self-government at Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., the chief negotiator for the Qikiqtani Inuit Association for the Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area’s Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement.

Connie Merkosak

Merkosak was a court worker in the Nunavut justice system before beginning the Akitsiraq program, and went on to article with the Maliiganik Tukisiiniakvik legal-aid clinic. She works with the Legal Services Board and as a senior court worker in Iqaluit.

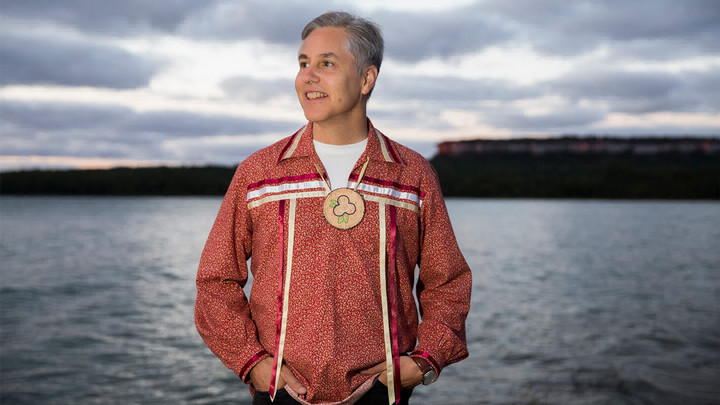

Aaju Peter

Before studying law, Peter took Inuit studies at Nunavut Arctic College in Iqaluit. She articled at the Ottawa law firm Nelligan, O’Brien and Payne, and was called to the bar in 2007. In 2011, Peter was inducted into the Order of Canada as a member for preserving and promoting Inuit culture and practices. Peter has been featured in several documentary films, including Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattoos (2011), Arctic Defenders (2013) and Angry Inuk (2016) where Peter and others strive to raise awareness of the negative impact that the North American and European Union anti-seal hunt stance and sealskin bans has had on Inuit ways of life. She was profiled in Twice Colonized (2023) which looks at the social and cultural trauma caused by colonization and follows Peter as she attempts to establish an Indigenous forum at the European Union. Peter teaches early childhood education, teacher training, as well as teaching adult Inuit to speak their language. Starting in February, she will enrol in the Aqqusiurvik progam delivered by Pirurvik, an Inuit-owned institute of Inuktut higher learning in Iqaluit.

Sandra Omik

Before attending Akitsiraq, Omik was the former chief commissioner of the Nunavut Law Review Commission. After graduation, she articled with Justice Canada in Iqaluit before being called to the Nunavut bar. She has worked as a Crown attorney in Iqaluit and as legal counsel to Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.

Madeleine Redfern

Redfern served as executive of Nunavut Tourism before law school graduation. After, she became the first Inuk law clerk to work for the Supreme Court of Canada. Redfern was mayor of Iqaluit, serving from 2010 to 2012 and again from 2015 to 2019. Her governance and volunteer roles include the Inuit Non-Profit Housing Corporation, Tungasuvvingat Inuit Community Centre, Wabano Aboriginal Health Centre and Inuit Head Start in Ottawa. She has been president of Amautiit: Nunavut Inuit Women’s Association, Ajungi Consulting Group, and chair of the Nunavut Legal Services Board. Redfern advised Canadian Nuclear Laboratories, co-chaired the Gordon Munk Arctic Security Program, and served on the Maliiganik Legal Aid board. She was also the executive director of the Qikiqtani Truth Commission, looking into the historical effects of past federal government policies on Eastern Arctic Inuit. In 2022, Redfern received a UVic Distinguished Alumni Award. In 2024, Redfern was appointed interim CEO of the Native Women’s Association of Canada.

Qajaq Robinson

Prior to studying law, Robinson worked as a youth officer for young offenders and was the head coach of the Nunavut junior girls’ basketball team. Following graduation, she articled at Maliiganik Tukisiiniakvik, clerked with judges of the Nunavut Court of Justice and then became a Crown prosecutor who worked the circuit court in Nunavut. She has worked as legal counsel at the Specific Claims Tribunal and was an Associate with Borden Ladner Gervais LLP in Ottawa. Robinson was one of the five commissioners chosen for the federal inquiry into MMIWG, where she interviewed hundreds of Survivors and co-developed the findings, calls for justice and final report. She also serves as on the board of Tungasuvvingat Inuit, a not-for-profit providing cultural and wellness programs to Inuit in Ottawa, as well as the Nunavut Independent Television Network.

Naomi Wilman

Before being accepted into the Akitsiraq program, Wilman was a youth worker who developed an Inuit Cultural Program for incarcerated youth. After being called to the bar in 2009, Wilman has worked practising family law in Nunavut. She has served as director of the Quality of Life Secretariat within the Nunavut Department of Health. After obtaining her law degree, Wilman completed a BA in psychology from Queen’s and Carleton universities and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in counselling psychology.

This article appears in the UVic Torch alumni magazine.

For more Torch stories, go to the UVic Torch alumni magazine page.